SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS 2025–2026

Part of the second floor is used to organize special exhibitions three times a year. Themes are taken from both Japanese folk art and archaeological fields.

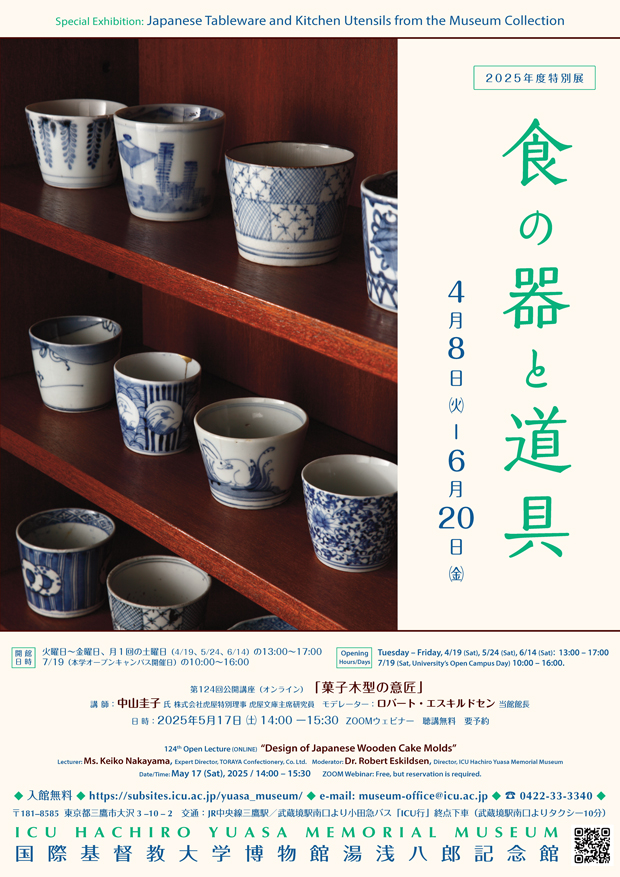

This exhibition introduces Japanese kitchen utensils and tableware from the Museum’s collection, featuring items from the mingei collection assembled by the late Dr. Hachiro Yuasa (1890–1981), the first president of the International Christian University, together with other Edo to Meiji period objects from the Museum’s acquisitions. Some 150 kitchen utensils for cooking, serving, storing and carrying, as well as tableware with various designs were selected for display. We hope that you will enjoy the variety of Edo to Meiji period kitchen utensils and tableware through this exibition.

There is a saying in Japan: “Any scrap of cloth big enough to wrap three azuki beans should not be discarded.” Can you imagine a time when people made use of every bit of waste thread, every piece of worn fabric? When parts of a kimono were torn, they were patched and covered with layers of cloth and stitched for reinforcement. Bedding cloth was made by sewing small pieces of fabric together. Worn cotton fabric was made into thin strips and woven with leftover thread, thereby transformed into a new and different fabric.

Before the spread of mass-produced items, much effort and ingenuity were devoted to the practice of recycling and reuse in nearly every aspect of daily life. For example, wooden cake molds and paper stencils show traces of careful repair. Moreover, the design and practice of using recyclable bottles for sake and soy sauce reveal a mindset that cherished objects and saw their long-term use as a virtue. Other examples include dolls and figurines made of sawdust, a by-product of woodworking, and hariko papier mâché dolls created from used paper, allowing for the utmost use of materials that otherwise would be discarded. The technique of repairing ceramics with gold-dust lacquer (kintsugi) has surpassed the boundary of repair, becoming itself an example of artistic creativity. Recently, kimono worn over generations and showing traits of countless repair and retouching, have gained recognition abroad, known as boro (literally, “rags”). Since ancient times in Japan, it was believed that a power beyond human conception resided in pieces of cloth, so children’s kimono was often sewn with pieces of fabric especially collected, with the hope to ensure a happy and healthy life for the child.

Dr. Hachiro Yuasa said: “Thinking it a pity to throw away materials so precious, and in response to the demands of a humble life, these bits and pieces of thread were made into cloth like this, the beauty of which has been so surprising to me.”* Here he speaks of the esteemed richness of spirit involved in the making of kuzuori (cloth woven with waste thread). The value of things may change over time, but the pursuit of our predecessors to make the most of every scrap and bit of thread challenges the standards of our contemporary world, directing us to consider that the life of things may exist in a different dimension.

It has been ten years since the United Nations adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, establishing 17 SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals). We hope that this exhibition will help reconsider the concept of sustainability through handcrafted items that make us think of the “life” of things.

*Hachiro Yuasa, The Heart of Mingei (ICU Hachiro Yuasa Memorial Museum, 2023), p.99.

* We will be hosting an Open lecture related to this special exhibition on September 27. [Details]

Riddle and other satirical ukiyo-e prints, requiring education and wit to decode patterns and symbols, as well as daily items designed with characters and words from the Museum collection, will be featured in our next special exhibition.

* We will be hosting an Open lecture related to this special exhibition on February 28, 2026. [Details]

SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS 2024–2025

It is said that “white” of the face powder, “red” of the rouge on lips, and “black” of hair and teeth-blackening (ohaguro) are the three colors that symbolize Edo period makeup. We have selected some 148 cosmetic utensils and related items from the Museum collection for this exhibition.

The Yuasa Museum opened in 1982 to commemorate the contribution made by late Dr. Hachirō Yuasa to ICU. Dr. Yuasa had collected and donated a wide range of mingei items to the Museum which included cosmetic utensils. Many were made during the Edo period—small jars used as hair oil containers, round bronze mirrors with handles often with auspicious designs on the back, and combs and hair ornaments with delicate designs.

In addition to the items collected by Dr. Yuasa, we have also displayed items that were acquired by the Museum over the past years: teeth-blackening utensils we rarely see today, portable barber’s chest, small rouge plates and palettes, and sets of cosmetic boxes and chests for storing utensils and brushes for makeup. Both simple black lacquered items used by commoners, as well as richly makie-decorated ones that comprise the bridal trousseau of upper-class family are shown in this exhibition, hoping to give a glimpse of cosmetic items used for the Edo period makeup.

* We released a video recording of the 121st Open Lecture, "The Transformation of Clothing in the Edo Period," on ICU OpenCourseWare. [DETAILS]

During the Meiji period (1868–1912) which followed the long Edo period (1603–1868), Japan embarked upon a period of rapid change, much of it derived from the introduction of new culture, technology and values from the West. After the opening of Japan (1854) and Meiji Restoration (1868), Japan sought to establish an equal diplomatic relationship with western countries. This led to the proactive adoption of things Western: in other words, the promotion of “civilization and enlightenment” (bunmei kaika). Politically, this meant the construction of a centralized nation committed to industrialization and military build-up; culturally, western elements were adopted in the lifestyle of the people, high and low.

How did people respond to this rapid array of political, social, industrial, and cultural changes? This exhibition focuses on Meiji period ukiyo-e woodblock prints, an artistic but also information media created in the Edo period that retained its popularity in the Meiji period. The Meiji ukiyo-e help us to understand how and why people were astounded by and attracted to new culture from the West. In addition, on display are some Meiji period daily use items from the Museum collection. We hope to show the many surprises encountered by people one after another during the Meiji period—the changes that led to the birth of modern Japan. At the same time, we introduce interesting features of Meiji period ukiyo-e that so vividly express the atmosphere of those days.

* We will be hosting an Open lecture related to this special exhibition on January 25. [Details]

PAST SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS 2023–2024

Katagami are stencils used for dyeing made from Japanese paper on which patterns are carved, the paper having been waterproofed with persimmon tannin. When dyeing using Katagami, the stencil is first placed on the fabric and a dye-resist paste made of rice is applied over it. After the fabric is dyed and the paste washed off, the areas covered by paste remain undyed forming white patterns. Katagami are used in the application of small figure designs on cloth (edokomon), printed silk (kata yūzen), as well as on light cotton cloth for yukata. The history of Katagami is long. Stencil dyeing employing the same techniques as today was already in practice during the Kamakura period (1185–1333).

Usually, one stencil is moved across a piece of material to produce a continuous design. Elaborate patterns can be made by using two or three stencils, which is called “double stenciling” or “triple stenciling.” Pattern-carving methods include push-carving, awl-carving, pull-carving, and tool-carving, with appropriate techniques used for different designs. Thread insertion, requiring supreme delicacy and high level of technique, is necessary to hold patterns in place. Most of the stencils are from the Shiroko and Jike areas of Suzuka city along the Ise Bay, and they are generally known as “Ise paper stencils” (Ise Katagami). They became popular during the Edo period (1603–1868) due to the patronage of the Ki Domain. There are stencils from areas other than Ise, such as Kyoto, Edo and Aizu as well.

This exhibition highlights the great variety of Katagami patterns and the sophistication and precision of carving techniques employed.

* We will be hosting an online open lecture related to the special exhibition. [FOR DETAILS]